Coaching the Teen and Junior Powerlifter: Long Term Athletic Development, Burnout, and Reaching the Ceiling Faster

Athletic excellence is getting younger and younger.

Read that again.

Erriyon Knighton won bronze in the 200m at the age of 18 at the 2022 World Championships, since then, he is has become the 5th fastest in history over that distance, however, is this indicative of him eventually being the fastest ever when he reaches his mid 20s?

In 2023, and really over the last decade or so, sports as we know it, have had phenoms come out of the woodwork and set the competition scene on fire for a short, but intense ride, almost comet-like.

I’ve been inspired to write about this topic for a few reasons.

The first, and most pertinent, is currently on my roster of 47, 10 are teen lifters and we can make that 14 if we stretch that to allow juniors, if we went back to last year, I had quite a few people age out of juniors so the same concept applies for them. So this topic hits close to home.

The second, and maybe more thought-provoking concept, is the fact that we are seeing athletes, not just in the sport of powerlifting, but other sports as well, enter the sport earlier and earlier and are competing with adults by the time they are 16-18 years old.

What gives? Has this always been the case? What happens to those elite kids after then exit their teen and junior years? Would I have been better off starting earlier?

Well, let’s see if we can answer that.

Part 1: Long Term Athletic Development

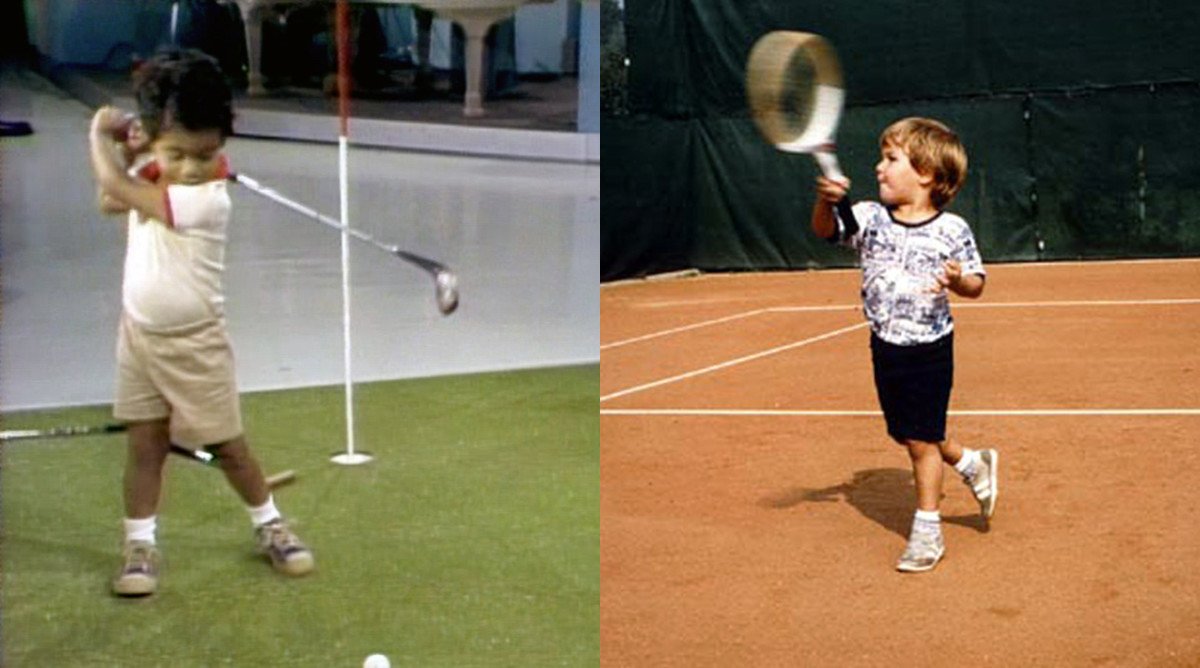

Pictured left, a young Tiger Woods, to the right, a young Roger Federer. David Epstein cited their development and their stark contrasts in his book, “Range”. He cited the fact that Tiger fell into the camp of early specialization, Roger fell into the camp of wide variety as an adolescent that streamlined into a singular focus when he entered his late teens.

When we see this term, what do we think?

I’ll tell you, when I see this, I immediately think of the pipeline of youth sports to professional sports. This is a good start, but it does not explain the whole story.

In the most basic sense, long term athletic development is a system of training, competing, and recovering with a longer term end-goal in mind. So, we are not trying to peak and be our absolute best in grade 8 league championships, but rather high school state championships or collegiate championships.

Does it always work out this way?

No way.

I think most people reading this article have started a sport and did not end up staying with said sport, for a host of reasons. So LTAD most times, will refer to overall athleticism.

I think most of us can at least conceptualize, that at age 5, it is usually not going to be appropriate to undergo an ultra-specific 5 day a week training regimen with periodization and peaking built into it. If you know that this is at least non-productive for long term development, you are virtually all the way there with LTAD.

Enter, early sport specialization vs. variety of sport participation.

Although these days the camps of each are seldom only on the extreme left or right of the arrow, over the years there has been quite the contentious debate on which is superior for likelihood of participation of sport at the “next” level, I say that in parentheses because next could mean college, could mean the pros, hell it could even mean high school.

In general, adopters of early sport specialization will cite the increase of skill acquisition, solidification of technique, and in general, understanding of whatever sport they are in, much earlier than peers around them. Pair that with a genetic build/drive for the sport in terms of aptitude and body type, generally, this method has merit.

However, the cons of which include, but are not limited to: early burnout, increased injury-risk in the chronic sense, and never giving another sport or discipline the chance to blossom due to so much emphasis on one.

The latter point, I think we all know someone, or ourselves included, that really poured themselves into a sport that they really were not built for and as such, did not have the resources or time to develop another because they simply ran out of time.

Adopters of variety at a young age will cite the development of different energy systems, different planes of movement, and general lack of burnout as the next season represents a new sport, not the same one in a different league.

However, the cons of variety usually will lead to skills developing slower and a distinct difference in peak ability. In other terms, it becomes a jack of all trades, master of none scenario, when taken to the extreme.

Let’s go back to our Tiger Woods vs. Roger Federer scenario and how it applies here.

Tiger started golfing at the ripe age of 2 years old, and never looked back.

His life from beginning to now, has been golf and will probably always be golf. It is hard to argue this earliest of early specialization model when he is the consensus most dominant golfer to ever pick up a club, becoming the best player on earth at the age of 21.

However, and forgive me as this is a bit off the beaten path, Tiger did not get there without controversy off the green as well as several major debilitating injuries that really have changed the course of his career. Hang on to this thought as we go on.

Now, let’s look at Roger Federer.

Known as one of the best tennis professionals ever, Roger grew up sampling many sports that according to my research included: skiing, wrestling, basketball, soccer, handball, and even skateboarding.

He narrowed his focus to tennis as he got older and ended up as the number 1 tennis player and enjoyed a career that spanned almost 25 years, retiring at the age of 41 with 20 Grand Slam titles to his name.

Again, hard to argue this approach, when it yielded a phenomenal athlete that was able, for the most part, to stay injury-free until the twilight of his career.

So, why is this tale of the opposing sides of the same coin highlighted?

Well, because I think that is what we are seeing in real-time with the sport of powerlifting and I am curious to dig into some of the detail.

Part 2: Has This Always Been The Case? Or Are We Just Noticing It More With More Coverage?

Perhaps the best example of precocious ability in powerlifting, at least in the modern sense, is Jesse Norris, who competed in 20 meets between ages 14 and 23, culminating in a 2033lb total at the age of 22.

Now, this is where my personal speculation starts to creep in here. Full disclosure of admitting biases!

In my opinion, these freaks of nature, have been around for quite some time now.

Are they proliferating? Absolutely.

Is this anything new? No, at least if we use the scape of 2010 to 2023, the era where raw powerlifting took off. If we want to go back even further, expand into equipped, we could cite Caleb Williams, Shane Hamman, and a host of others that exploded on to the scene at a young age and either burned out or moved on just as quick.

With the advent of modern media, you don’t need a news team to document rare or incredible feats. Pressing record on your iPhone and putting it up on Instagram with a song of your choice is literally a 30 second endeavor.

With the sport growing, we are just seeing it more often.

However, I think this speaks to another concept in that the sport is more accessible than ever. You do not need to be in touch with a local coach to enter a meet.

You don’t need to peruse the web for hours to find a competition.

You can click on any YouTube video that will explain the rules of any federation within a minute of searching.

I can go on and on here, but with this, comes earlier and earlier entry to the sport.

To compare this in a somewhat comparable sport, let’s checkout CrossFit.

Sam Briggs, won her first CrossFit Games in 2013, at the age of 31. It was not uncommon to see winners and podium members be in their late 20s, early 30s.

Emma Lawson, in the most recent CrossFit Games, was in the lead for the majority of the competition and ended up in 2nd place at the age of 18. Mal O’Brien did the same the year before. This is becoming the norm.

In a sport like CrossFit, which is predicated on that concept of being a jack of all trades, a master of none, it makes sense that you need longer times of training to develop the skills necessary. In the inception days of CrossFit, people migrated to it from their ending of collegiate sport or their search of a new competitive outlet in lieu of collegiate sport. Almost a fall back option.

Nowadays, younger kids are choosing CrossFit as their sport.

Again, the more accessible the sport is, the more likely it seems youth are to be involved. And if there is a barbell sport that is accessible, this has to be the highest or second highest on the list with full on media coverage on every social media there is, and professional coverage at that.

Getting back to the main point of this sub-section, these kids have existed for a while, however, there is more and more incentives to get into these sports as opposed to the core team sports then in years passed and with that, comes the migration.

So to summarize, is this happening more often? Yes. Is it anything we haven’t seen before? No.

Part 3: What Happens To People Who Started Earlier, After Initial Success? Would I Have Been Better Off Starting Earlier?

Seventh Woods raised signs of being the next great prospect at the age of 14, although eventually finding his way, he never materialized into the player he was projected to be at a young age.

This is the main issue that I think needs a deeper examination, a more formal one that I do not have the means to perform.

Again, speculation here so bare with me.

It seems as if we historically conflate biological age, with training age, and that is the concept that sometimes throws us awry.

But what does this mean? Does your actual age not matter? Well, it does, but only to an extent.

The easiest way to describe this, is comparing a young lifter who has already done 10 meets before the age of 20, with most of those being high level national meets, to an older lifter who has done just a few meets but is substantially older.

You see this all the time in other sports, the one that immediately comes to mind is basketball.

Luka Doncic, although only 24 years old, is coming up on year 9 of professional basketball. Starting at the age of 16 for Real Madrid, it makes sense why he was not like other rookies during his first year in the NBA.

It is somewhat common to see 2 players be the same age, but one has been playing in the league almost incomprehensibly longer than the other. If two players are equal in their base, the one with more experience usually is the better player in these scenarios.

When we are looking at powerlifting, unfortunately, we don’t have this kind of data ready to go at our fingers, I am aware OpenPowerlifting exists, however, we don’t have the stories associated with why a career was terminated early, or why a particular athlete stuck with it, or why they stopped progressing. I am a big fan of the adage, “Numbers don’t lie”, however, they don’t tell the whole story in scenarios like this.

Now, my working theory is the following:

With lifters entering the sport earlier and earlier, and specializing to boot, they are simply reaching their ceiling faster and at an earlier age than their older counterparts.

With this, comes better results as a teen or junior, however that rate of progression, seemingly is not directly correlated to success in the open-aged division. Context matters here, as there are some teens who can win the open division, I am referring more so to when they actually are aged into the division.

The more specific an athlete trains at a younger age, and the more frequently an athlete competes at a young age, the more likely they are to burnout early, maladapt or experience slowed progression at an earlier overall age.

Lastly, it seems as if these athletes are more prone to termination of sport early compared to others who started later, after a career in another sport and that could be for a host of reasons included, but not limited to: lack of progress that matched initial ascension, injuries developed from a super specific approach, lack of excitement in training, and what I see in my position be the most prevalent, a general uptick in stuff outside the gym that effects their ability to do what they want to do in the gym.

In the next section of this article, we will talk about what this looks like in terms of application, but to give this concept it’s flowers, I want to try to answer the age old question of people who were bit by the powerlifting bug.

Would I have been better, if I started earlier?

Impossible to tell with exact certainty, however, I will use my own career as an example.

I have been weight training since I was 13 and recently turned 26. I have not gone more than 7 days without resistance training for 13 years.

My first olympic weightlifting meet, I was 19.

My first powerlifting meet, I had just turned 20.

Within that time frame, I have been able to do the things I have done, which I do not think are remarkable, but certainly am no slouch in terms of overall competition, and have only gotten better with age and feel like I still have not even touched my capacity.

For me to say, if I would have started at 17, I would be so much better, would be lying to myself as so much life changed for me during that time.

I was playing 3 sports in high school, eventually graduated and moved away, dealt with personal issues, had to learn things more applicable to adult life, etc… Having to do all that and try to be a competitive and structured powerlifter probably would have burned me out before college ended.

You see, as you go on, and I remember these days clearly, the infinite time you have in the gym, begins to dwindle. The almost endless energy store you once had, begins to decrease in capacity. Your once superhuman ability to recover, is now a fraction of what it once was. You having to do homework at the end of the day as your biggest stresser, turns into how are you going to make it to the gym today after working, attending class, and needing to go to the grocery stores since you are out of supplies?

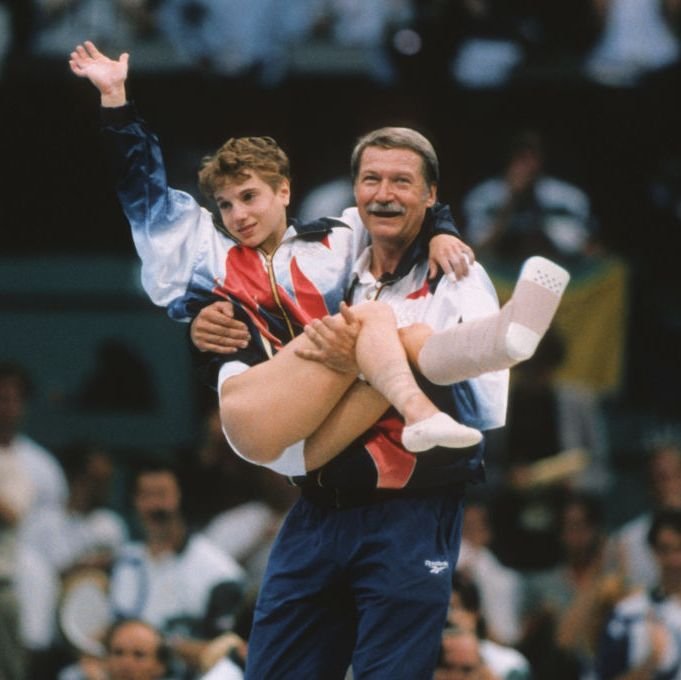

This is not a decree that kids have it easier, actually quite the pro-youth sentiment. However, it is realistic to say that if there’s any time to double down on a competitive career, it is then. Look at Olympic gymnasts, particularly on the female side, who put all their resources into a career that will ultimately peak out at the age of 16, for most.

Kerri Strug, who competed in two Olympics before the age of 20, is remembered for her heroic performance in 1996 in Atlanta, vaulting on a severe leg injury to help the Magnificent Seven team take Gold. Strugg retired shortly after the ‘96 Olympics and exited to a “normal” life.

Coming back to powerlifting, we have to keep in mind, raw lifting, again, in the modern sense, has only been around since the early 2010s, so we have only a few examples of what precocious talent materialized into after initial succcess.

Jesse Norris, who we cited earlier, did his final meet as a junior in 2016 and has not made a return to the platform since.

Jesse, had already done 20 meets at this point mind you.

That is 20 meet preps.

20 peaks.

20 times you have to navigate small injuries.

20 times you are held to the standard of your best, which for him, was the apex of what we had seen at the time.

The fact of the matter is you probably started when you were supposed to and your career will end when it is supposed to.

There are outliers for a reason, they do not reflect the average.

Part 4: Coaching the Teen or Junior Powerlifter

It took you all of that, to finally get to here? Although I tend to get pretty excited writing about my passions, I actually do think all of that context matters.

Over the years, I have been trusted with working with a ton of teenagers and young adults and as such, I think I have a solid system of how to avoid the pitfalls of early termination of competition as well as keeping the expectations appropriate for each level an athlete enters.

The system that I touch upon in our first few blocks together kind of looks like the following, for some, other points are emphasized over others, but seldom have I not provided guidance upon each variable.

We are not out to peak at age 16, we are aiming to peak in our mid 20s.

Now, this is not to say, when an athlete turns 25, it is time to turn up the volume because time is running out. It is more so to set the precedent that I am not interested in spitting them out after 2 years of maniacal workload for a shot at a teenage record. If those things happen, they happen organically. I find when this is the expectation from day 1, it is easier to explain your approach to a younger athlete who usually needs to be convinced to stop doing so much instead of trying to more.

Social media is a game of exceptions not the standard. If you want to be a powerlifter, you compare your meet results, not your showcase lifts in the gym.

This is the hardest one to navigate. Nowadays, kids are doing crazy things in the gym and are being rewarded with sponsorships, small-scale fame, and plenty of clout. Although this really was not big when I was growing up, I can understand why a kid would want to train with straps on whippy bar and take heavy singles every workout. The average person does not care about your total, but if you can say, “I deadlift 700lbs” or, “I can bench 405lbs”, the average person is not going to care if it is in a meet, without straps (deadlift) or paused (bench). Social media has a way of showcasing the exceptions and not the average. We don’t see someone’s 460lb PR as impressive in his meet because someone his weight class went viral on SportCenter doing 200lbs more, albeit with straps on a deadlift bar. I like to draw the line in the sand with my guys and girls in that you either want to be a social media lifter or a powerlifter, you can blend the two, but if you want to perform well in meets, the second option has to always be in the forefront.

You need to love lifting before you love powerlifting.

This one is becoming few and far between. At Team Hogan, I try my best to preach loving the game, the process, more so than the outcome. How I like to frame it, is if Instagram was terminated tomorrow, and no one would ever know about what you did in the gym or at meets, would you still lift? I want the answer for my young kids to be a resounding yes, because lifting has a lot of benefits outside of competition for health and longevity and I want them to at the very least, have good habits for later into life, should they decide competing is no longer for them.

There is always going to be another competition.

Now, there is exceptions to this. If an athlete has a chance to win high school or teen nationals, I am not going to intentionally hold them back at the meet because I would rather them win an open title, that is absurd. However, in the local meets we do, we have to realize that for every send it attempt we do, the more we open the door for: injury, a poor outlook on what was a great day, and a general habit of missing lifts in meets which can be hard to shake once you get going. For a lifters first meet with me, I will not push to the apex as a 6/9 day with 3 missed third attempts feels a lot worse than going 9/9 and maybe you had 2.5-5kg to spare on all 3. Don’t believe me? Watch people’s disposition when they miss a third.

Your rate of success early on, cannot be expected to be sustained.

I am fortunate enough to see a lot of kids get really strong, organically, very quickly. However, it cannot be expected to sustain this kind of output for much longer than a 2 year span. Just because you put 200lbs on your total in year 1, does not mean that will happen in year 2, year 3, etc… If that were the case, every person would be totaling 2000 within 5 years.

All PRs are good PRs.

Just because you only put 10lbs on your squat instead of 30lbs, that does not mean your training cycle was a failure. I like to point out my older clients who have been in the game for quite sometime, who scratch and claw for 5lbs on a lift within a 6 month timespan, and like to point out that any time you are progressing you should not be too picky at the rate, as not progressing will feel even worse for you.

We will not and cannot get too specific, too soon.

It is normal for a younger lifter to see their fave lifter on Instagram, hitting comp singles each workout, hitting the comp lift multiples times a week, and be rather disappointed when that is not their approach. We just talked about why early specialization is not the best thing for long term commitment to a sport for most, so this is what that looks like in powerlifting. All the people that I know, who exited the sport early, all trained comp SBD multiples times per week, went very heavy, very often, and never did accessory work or variation to the extent of it actually being beneficial. In fact, most of my young kids do not reach 2x per week comp squat frequency until the end of year 1 or year 2, when only a single day is beginning to not move the needle as much. I try to preach to care about things like your lateral raises, your leg presses, your dips, just as much as SBD stuff.

You have to trust that I have your best interests at heart.

Early on in my coaching career, I would get off on a bad foot with my teenage lifters for a host of reasons, mainly due to lack of trust. Things such as training being “too light”, them constantly thinking they can do more, rationalizing why they should do things differently, etc… The fact of the matter here, is I trust my experience lifting and competing at high level for 5 years, my 6 years of coaching experience, my bachelor’s degree in exercise science, over what a kid sees in a YouTube video from an influencer who has not done a meet. If you do not link I am doing the things I do to get you stronger and maintaining your health, then I do not think we are a good fit and it may speak to you may not be ready for high level coaching, which, is really something it itself, for another date.

It is not a sin, to want to do another sport.

I like to treat my kids as adults in the sense of, you can and should do another sport this early, but is your decision whether you want to follow through with that, or not. I like to be realistic in that we can’t push both at the same time, so when the season rolls around, we lift for maintenance, the other sport takes precedent, however, if an athlete is training for a national meet, now is not the time to be playing full court 5s in basketball.

Lastly, surround yourself with positive influences.

This sport is very unforgiving, and if you surround yourself with people who don’t allow you to experience joy, are constantly nitpicking you, or are simply a bad influence on you and your training, you will almost surely be out of the sport as quickly as you entered it. The common notion I see, is the guru of the athlete’s gym, does not agree with my plan, and convinces my athlete to stray away from it. Not only is this disrespectful to me, but it is very counterproductive to everything we just laid out earlier. I am well aware I could give my kids singles on all lifts and watch as I take the credit for their progress over the next year. But if that was to occur, are you also willing to take blame when the same approach leads to injury and lackluster training in year 2? Are you willing to take blame when that same approach leads to termination of participation in year 3? When you are a kid, you can only control so much, so I like to make sure they are influenced from the correct resources as much as I can, because I know how powerful outside influences can be on molding a personality.

So, I figured to close this, we use an actual practical example of a long term model I have adopted for one of my athlete’s who came to me at the age of 15, Logan Allaire.

In just one year, Logan Allaire has set an unofficial American record, put ~94lbs on his total, lifted in 4 meets (only peaked for 2 of them), and competed nationally. After meet #4, we extended his off-season.

Let’s compare his third block with me, to the most recent, block 13.

Although this is not the entire program, you will see there is a precedent on variation. His frequency is somewhat atypical of someone that age, however he was used to it coming to me. This was in prep for his first meet, you will notice the total set count is very low on most days, with no barbell lift exceeding 3 working sets, and there is lots of movement variation: pauses squats, close grip benching, RDLs, machine work.

Although we are further along, we actually trimmed off a training day, introduced load caps, but still are featuring a very low total weekly set count. We also are not biasing a ton of volume to lower body pressing movements as we identified the fatigue debt associated. This plan came about after dealing with hip injuries in his nationals prep and we have been fortunate enough to PR virtually every block since then, with this approach. Prepping for meet #5.

You will notice that, although his frequency is high, it is not specific. We actually still have never pulled competition deads twice a week, have never competition benched 3x per week, and only the final 3 weeks of a meet, do we competition squat twice in a week.

This approach yielded an unofficial American record squat, and an 11th place finish in the US at High School Nationals, while maintaining the adherence of the values I just laid out.

We talk all the time about where he stands now versus where we will be in the coming years and what to expect when he has more and more responsibilities per week, which he is learning now working at Targét, pronounced like “tar-jay”.

He will be competing later this year, at an undisclosed location, at an undisclosed date, however, we have a firm understanding of this meet is to simply establish a bridge between Nationals, where we are fully intending on leaving with a medal. We will ramp things up for that meet, as it will be his last chance to do so. And we will probably pull back just as much when it is over.

Part 5: Should I Coach Teens and Juniors?

Haley-Jane Tuplin and Grace Poirier competed in their first meets as teenage lifters earlier this summer.

Well, your intentions for their career have to be in the right spot and you better be ready to be a mentor as well as a coach. We were all teens and young adults at some point, the things you deal with, the things you feel, are unique to that time period, so you have to be lenient to an extent.

If you believe in a very “old-school” approach of negative reinforcement and do not try to meet these younger people halfway, you will not send the message to other’s that you are fit to handle this demographic. Oh, and I have seen this happen too often, if you are taking a teen or junior on, and it is their first meet, you better be there handling them. I am sure people have valid reasons, but if you do not, I implore you to make the time to be with them for meet #1. Every meet I go to, I am helping someone out because their coach couldn’t make it and they do not know what to expect, which tells me they were never prepped for the ins and outs of the sport to begin with.

Above all else, be considerate and do not be afraid to make the conservative call, if necessary. We are not in the business of treating kids like NFL running backs, letting them run wild for 3 years and moving on to the next. I cannot wait to see my teens blossom into young adults, my young adults into grown adults.

I hope you all took something from this, and always and forever.

To Utopia,

Erik